The team at King’s College London showed that a chemical could encourage cells in the dental pulp to heal small holes in mice teeth.

A biodegradable sponge was soaked in the drug and then put inside the cavity.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, showed it led to “complete, effective natural repair”.

Teeth have limited regenerative abilities. They can produce a thin band of dentine – the layer just below the enamel – if the inner dental pulp becomes exposed, but this cannot repair a large cavity.

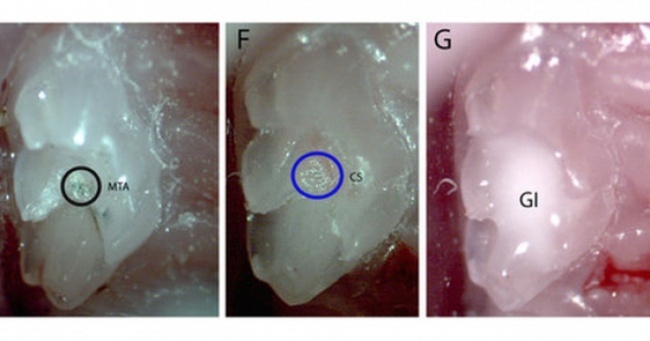

Normally dentists have to repair tooth decay or caries with a filling made of a metal amalgam or a composite of powdered glass and ceramic.

These can often need replacing multiple times during someone’s lifetime, so the researchers tried to enhance the natural regenerative capacity of teeth to repair larger holes.

They discovered that a drug called Tideglusib heightened the activity of stem cells in the dental pulp so they could repair 0.13mm holes in the teeth of mice.

A drug-soaked sponge was placed in the hole and then a protective coating was applied over the top.

As the sponge broke down it was replaced by dentine, healing the tooth.

New treatment

Prof Paul Sharpe, one of the researchers, told the BBC News website: “The sponge is biodegradable, that’s the key thing.

“The space occupied by the sponge becomes full of minerals as the dentine regenerates so you don’t have anything in there to fail in the future.”

The team at King’s is now investigating whether the approach can repair larger holes.

Prof Sharpe said a new treatment could be available soon: “I don’t think it’s massively long term, it’s quite low-hanging fruit in regenerative medicine and hopeful in a three-to-five year period this would be commercially available.”

The field of regenerative medicine – which encourages cells to rapidly divide to repair damage – often raises concerns about cancer.

Tideglusib alters a series of chemical signals in cells, called Wnt, which has been implicated in some tumours.

However, the drug has already been trialled in patients as a potential dementia therapy.

“The safety work has been done and at much higher concentrations so hopefully we’re on to a winner,” said Prof Sharpe.

This is only the latest approach in repairing teeth – another group at King’s believe electricity can be used to strengthen a tooth by forcing minerals into the layer of enamel.

Minerals such as calcium and phosphate naturally flow in and out of the tooth with acid, produced by bacteria munching on food in the mouth, helping to leach out minerals.

The group apply a mineral cocktail and then use a small electric current to drive the minerals deep into the tooth.

They say “Electrically Accelerated and Enhanced Remineralisation” can strengthen the tooth and reduce dental caries.